There is (no) Anthropocene, CoCA, Otautahi. With Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux with Colleen Coco Collins, Janine Randerson and Arielle Walker, and Virginia Were

December 2025- Jan 2026

Attempting double refraction (right wall), 2025, digital print of pinhole photographs, 6000mm x 600mm. Photo: Owen Spargo

Attempting double refraction (right wall), 2025, digital print of pinhole photographs, 6000mm x 600mm. Photo: Owen Spargo

There is (no) Anthropocene responds to the controversial 2024 decision by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) not to classify the term Anthropocene as a formal geological epoch. Anthropocene is a broad term used to describe this era of accelerating human impacts on Earth, which are causing all five of our planet’s systems to become dangerously unbalanced. The decision came after more than a decade of research by the Anthropocene Working Group, which concluded that radioactive fallout from hydrogen bomb tests in 1952 was the best marker of humanity’s profound impact on our planet. Other scientists disagreed on the start date. Despite the group’s rejection of the term, it continues to be useful, widely used, and hotly debated – in the arts and humanities – as well as in the sciences.Importantly, the decision raises questions about the complexity of defining when the Anthropocene began. Was it as recent as 1952? Was it much earlier – at the dawn of agriculture? Was it fossil-fuel-driven industrialisation? How do we consider humans as part of nature? What should define this moment? With these questions in mind, the artists in this exhibition present new lens-based and sculptural works exploring the intersecting stories of two historic mining sites in the northern hemisphere, the current government’s push to reinvigorate petroleum and mineral exploration in Aotearoa New Zealand, and the impact of extreme weather on T?maki Makaurau Auckland’s west coast.

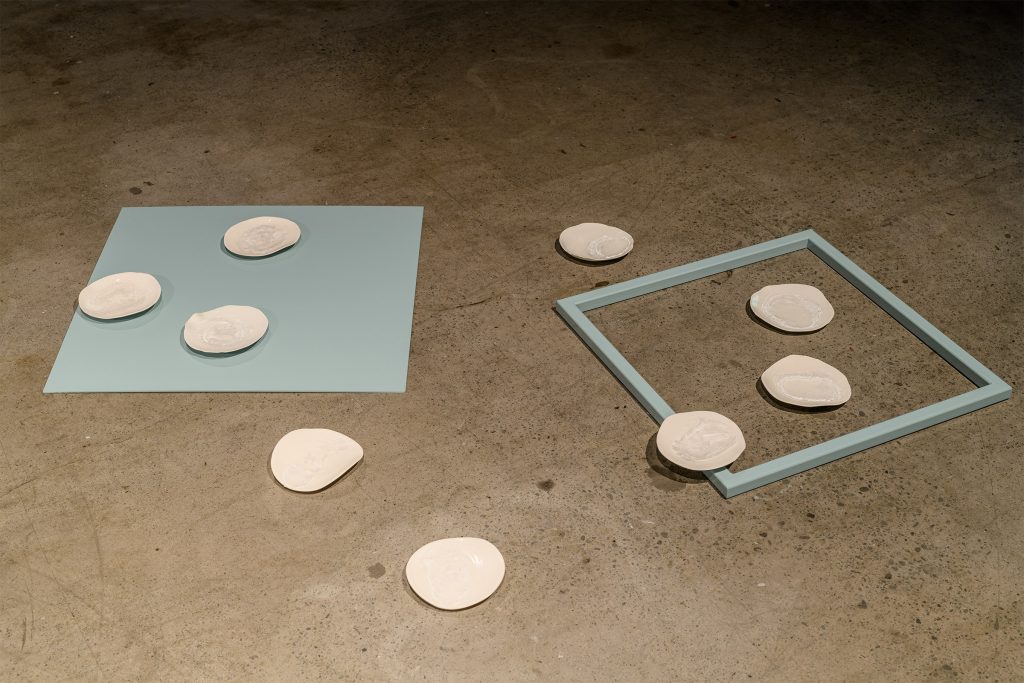

During the 1950s, atomic bomb testing caused what is now called ‘the bomb spike,’ an alteration of the chemical composition of Earth, which is evident in oceans, lake sediment, coral and teeth. People born in and after the 1950s have increased amounts of carbon-14 in their teeth. In Gnash, Shelley Simpson responds to this knowledge, using calcium carbonate extracted from eggshells to explore the way in which chemical bonds manifest and crystalline structures accrete through the process of evaporation. The thirty-two teeth in a human mouth are represented by the same number of small, ceramic discs holding calcium carbonate crystalline formations. In a large, suspended disc, the process occurs live over the course of the exhibition as the dry air in the gallery space encourages evaporation of calcium-rich liquid and crystal formation.

In Iceland, another form of calcium carbonate occurs as the very hard crystal, Iceland Spar, which was mined at the Helgustaðir mine in East Iceland from the 17th to the mid-20th century. Iceland Spar has the remarkable ability to split light into a double refraction, a property that led to polarised light microscopy, which advanced the study of the properties of materials. During a residency in Iceland in May 2025, Simpson made the work Attempting double refraction – a series of pinhole photographs, using a thin sliver of Iceland Spar as the camera’s lens.

(text from the floorsheet – full text here)